The History of Fort Frontenac

On July 12, 1673, the Gouverneur of New France, the Comte de Frontenac, arrived at the mouth of the Cataraqui River to meet with leaders of the Five Nations of the Iroquois to encourage them to trade with the French. While the groups met and exchanged gifts, Frontenac's men hastily constructed a rough wooden palisade on a point of land by a shallow, sheltered bay. On that day, Fort Frontenac was founded. Its colourful history, which has spanned three centuries, is being revealed today through archaeology.

Frontenac's aim in establishing the fort was to control access to the fur-rich Great Lakes basin and the Canadian Shield, thereby controlling the highly profitable fur trade. Furthermore, he and his colleagues hoped to benefit personally from the venture. To the most trusted of these associates, Robert Cavalier, Sieur de La Salle, Frontenac granted the fort and surrounding lands in seigneury, reserving for himself the right to trade at the fort.

La Salle used the fort as a base for his explorations into the interior. By 1685 the wooden palisade was becoming a fortress with walls of local limestone, square stone bastions, and a complex of buildings within the walls. A habitation was developing to the southwest of the fort along the lakeshore. According to maps and descriptions of the period, there were several habitant houses, an Indian village, a convent, and a Recollet Church. It seemed as though the outpost of New France was off to a good start.

La Salle, however, had grander ideas than to remain as simply seigneur of Fort Frontenac for the rest of his days. His destiny was to explore the lands south of the Great Lakes in search of furs. In 1682 he did not return to the fort, and the settlement fell into the hands of his creditors. They were interested only in the fur trade, and the habitation was ruined.

The fort's shaky position was further weakened by the outbreak of fighting with the Five Nations, spurred on by the conflict between the French and the British for control of the fur trade. The French government increasingly questioned the expense required to defend a post the usefulness of which was uncertain. In 1688, the garrison was attacked by the Iroquois, and 93 men died of scurvy, confined to the fort by a long siege. The following year, the garrison was instructed to raze the fort and return to Quebec: they set charges in the walls and departed.

By 1695 the war had ended, and Count Frontenac set out with a force of 300 soldiers, 160 habitants, and 200 Indians to restore the fort.

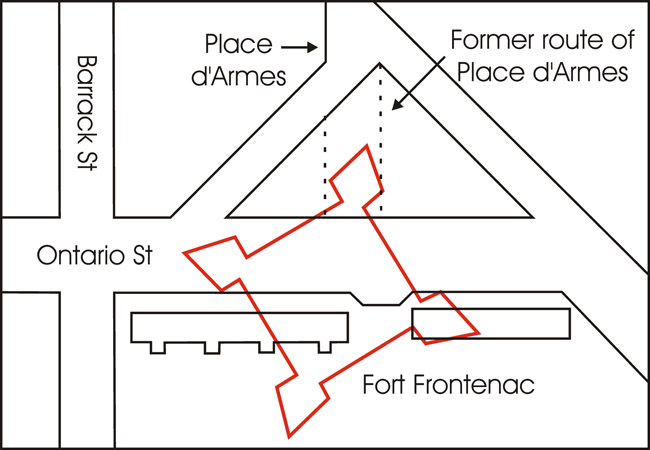

Over the next fifty years the fort was manned by a small garrison. Trade continued, but became increasingly unprofitable; various observers noted that the fort was dilapidated and outmoded. During the tense period preceding the Seven Year War (1756-1763) with the British, the French attempted to remedy the situation by increasing the size of the garrison, installing gun platforms on the ramparts, and adding new barracks. Their effort was in vain, however, for in August of 1758, a British force of 3000 men commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Bradstreet assaulted the fort. The vastly outnumbered French garrison of 110 men surrendered after three days; the fort was ransacked and abandoned.+

For twenty-five years the fort lay abandoned apart from the occasional visits by Natives and the activities of independent fur traders. The usefulness of the fort was once again perceived when the British were forced to move their civilian and military establishment from American soil at the end of the American Revolution.

In 1783, Major Samuel Holland was sent to survey the condition of the fort, and in the same year temporary barrack facilities were constructed. A townplan was laid out in preparation for the arrival of Loyalist settlers: the streets of Kingston still follow this plan. Soon warehouses and wharves occupied the shores where once Indians had camped and French settlers had tried to wrest their living from the heavy clay. The fort served as the main British military base for the eastern end of Lake Ontario until it was deemed obsolete after the war of 1812, at which point it was replaced by the Tete-de-Pont barracks, which now bears the name Fort Frontenac.

Archaeology at Fort Frontenac

Since the fall of 1982, the site of Fort Frontenac has been the scene of an intensive program of archaeological and historical research. The investigation, sponsored by the Cataraqui Archaeological Research Foundation, has received funding through a number of federal, provincial, and municipal agencies, corporate sponsors, private memberships, and donations.

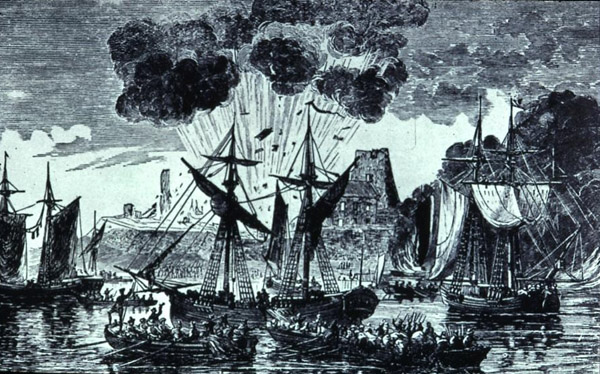

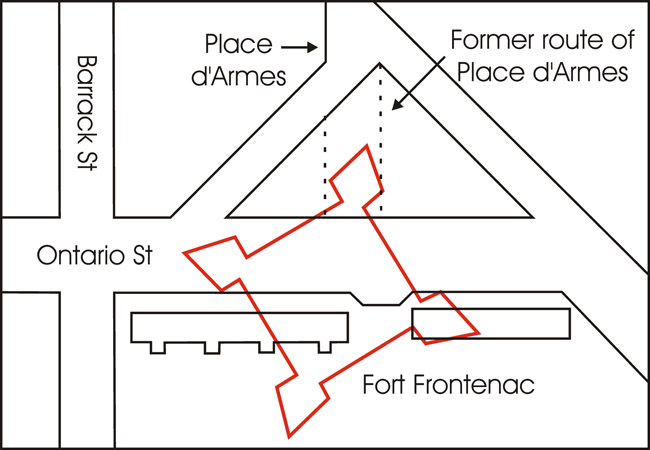

Archaeological and archival research have placed the original Fort Frontenac at the confluence of the Cataraqui River and Lake Ontario in downtown Kingston. The fort lies beneath and adjacent to the intersection of Ontario and Place d'Armes Streets, and extends east from the intersection under the present Fort Frontenac complex. Due to its location, only a small portion of the site, specifically the northwest bastion and adjacent curtain walls, can be investigated archaeologically. During the spring of 1984, the City of Kingston redesigned the intersection providing access to the eastern end of Place d'Armes for the purpose of excavation and, ultimately, reconstruction of the northwest bastion of Fort Frontenac.

Structural and artifactual data recovered during field work have provided important details relevant to the development and utilization of the fortification and surrounding area.

The northwest bastion, or Bastion St. Michel, has been the primary focus of the investigations at Fort Frontenac. Excavation within the bastion has revealed structural elements important to establishing an accurate relationship between the physical remains of the fort and data provided by the various historical plans available to researchers. Unfortunately, various areas of the bastion have been destroyed through the placement of utilities running across the site.

Located within the bastion were the remains of a pit excavated into bedrock, which was filled with soil containing numerous fragments of charcoal, wood, and mortar. Artifacts recovered from the fill included trade beads, a trade axe, and coarse red earthenware, all of which suggest an eighteenth century French context. The function of the pit itself is as yet undetermined.

The realignment of Place d'Armes enabled archaeologists to excavate the area of the north curtain wall constructed by La Salle circa 1686. This 60 cm thick masonry wall replaced an earlier log palisade, which was evident immediately adjacent and interior to the north curtain wall. The remains of approximately ten vertical posts or pales were also excavated, and part of the dry moat or ditch located on the exterior of the north curtain wall was evident in the form of an excavation into the bedrock. This latter feature, first depicted on the 1685 French plan of Fort Frontenac, extended from the midsection of the west curtain wall around the northwest bastion and along the full length of the north palisade. The mixture of eighteenth and early nineteenth century cultural material within the fill indicates that the ditch remained open until sometime after the reoccupation by the British in 1783.

Other features exposed on the interior of the north curtain wall provided evidence of structural development prior to and subsequent to construction of the masonry wall; these structures have been identified from French plans of Fort Frontenac. Initially, the area contained soldiers' barracks, but by at least the 1720s the barracks had been replaced by a trader's living quarters. Artifacts from this area include trade beads, copper kettle fragments, and fragments of bottle glass.

Excavation was also conducted on a second limestone wall lying parallel and adjacent to the exterior of the north curtain wall. This wall was built in the dry moat/ditch at a width of approximately 120 cm, and evidence provided by early British plans of the fort suggests that it was part of a temporary barrack structure erected by the British in the late 1700s. Due to the extent of various later disturbances, the recovery of further elements of this structure was restricted.

To the north of the fort, very fragmentary remains of the French stables were exposed. Construction of the British Issuers' Office, circa 1824, and the Grand Trunk Railway in 1858 destroyed all evidence of the stable except for one course of the stone foundation and several areas of mortar staining. Part of a large squarish pit dug into the bedrock, adjacent to the stables, was excavated and has been temporarily identified as a subterranean powder magazine.

Excavations along the western edge of Ontario Street revealed a complex of masonry walls relating to Fort Frontenac and to subsequent nineteenth century development in the area. The most easily identifiable foundations are those of the 60 cm thick west curtain wall, constructed by La Salle in 1680. Abutting this wall are the fragmentary remains of the trader's store house, which came into use circa 1726; while only a small area of the trader's house survived subsequent destruction, archaeologists were able to recover artifacts directly associated with trading activities. The store house was partially destroyed by the construction of a barrack building erected by the French circa 1755-1756, and by the construction of a limestone house circa 1828.

The French barrack building was re-utilized by the British between 1783 and circa 1816, during which time several structural alterations occurred: a rectangular masonry feature appended to the exterior of the barrack wall was one such alteration. The fill deposits within this feature contained a wide variety of late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century artifacts.