Who was Molly Brant?

A very general history of the life of Molly Brant can be found in a number of books and journal articles written about her. There also exists archival material in the form of letters and journals providing information on specific events in which she was involved. Unfortunately, this provides little detail regarding her life prior to the American Revolutionary War, and even less regarding her later years in Kingston. Who was Molly Brant, also known as Koñwatsi-tsiaiéñni? This is a question asked all too frequently when the name is mentioned. She is most often recognized in reference to her brother, Joseph Brant, leader of the Mohawk people and founder of Brantford. She was, however, famous in her own right.

Life in the Mohawk Valley

It is generally accepted that Molly was born in 1736, possibly in the Ohio Valley (Wilson 1976: 55; Graymont 1979: 416) where her family lived for some time. Her parents seem to have been Margaret and Peter, who were from Canajoharie, the upper Mohawk village. They were registered in the chapel at Fort Hunter, the lower village, as Protestant Christians. Peter died while the family was living on the Ohio River, so Margaret and her two children, Molly and Joseph, returned to Canajoharie. Margaret then married Nickus Brant, who may have been part Dutch. Some scholars have suggested that the use of Nickus Brant's surname indicates some non-Native ancestry (Green 1989: 236).

There continues to exist a great deal of confusion as to the identity of Joseph Brant's father. Assuming that Molly and Joseph had the same father, confusion also arises in recognizing Molly's father. If we consider traditional Iroquois society, however, the identity of the father is insignificant in comparison to that of the mother. Iroquois clans are matrilineal, meaning that kinship is based on the maternal or female line. Each member of the Iroquois League, which includes the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Mohawk and Tuscarora, have their own clans. The Mohawk have only three: turtle, bear, and wolf. Each clan owns a number of personal names, which are passed on when a child is born. The child receives a name belonging to the mother's clan. In Molly's time, when a chief died, the clan mother, in consultation with other women in the clan, would choose the man who would assume the appropriate name and become the successor to the deceased chief. The clan mother would often choose a man of her lineage and of that of the deceased chief (Tooker 1978: 424; Graymont1976: 31; Thomas 1989: 143). With traditional European societies being patrilineal, it is easy to see why earlier historians have dwelt upon seeking out the identity of the father.

Multifarious Mohawk Chiefs have been suggested as either grandfather or father to both Molly and Joseph Brant. Names mentioned include Sagayean Qua Tra Ton, Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow of the bear clan (grandfather, Fenton 1978: 310), and Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row (Theyanoguen) or King Hendrick of the wolf clan (grandfather, Fenton & Tooker 1978: 474; Graymont 1979: 416). There is no known proof of any of these relationships, and certainly no league chief or sachem status was bestowed upon Joseph. As a note of interest, the latter two visited the Court of Queen Anne in London in 1710. Their petitions, which were presented to the Queen, resulted in the construction of Fort Hunter and the Mohawk chapel at Fort Hunter. In addition, a presentation of a gift of silver communion plate was made by Queen Anne to the Mohawk people (Fenton & Tooker 1978).

Nickus Brant, Molly's step father, owned a substantial frame house, lived and dressed in the European style, and, interestingly enough, included William Johnson as a close personal friend (Green 1989: 236). Although not much is known of Molly's life at Canajoharie during the 1740s and 1750s, from her infancy through her teenage years and into her early twenties, it is likely that she lived in Nickus Brant's house. She was well educated in the European ways of life, with her formal education likely taking place in an English mission school, as she learned to speak and write English well (Wilson 1976: 55; Graymont 1979: 416). It is also likely that she met William Johnson on more than one occasion through this period.

Molly Brant's political activity began when she was 18 years old. In 1754-1755 she accompanied a delegation of Mohawk elders to Philadelphia to discuss fraudulent land transactions (Green 1989: 237; Graymont 1979: 416). This trip may have been part of her training in the Iroquois tradition, for she was to become a clan matron (Thomas, 1989: 143; Graymont 1976: 31). The Mohawk women not only chose the chief, they also held economic power, controlling the use of agricultural land; they therefore controlled the food supply, which provided them with the ability to veto warriors decisions. They were thus also able to apply themselves in a political role (Green 1089: 236).

William Johnson was tremendously successful in carving himself a niche in eighteenth century North America. He acquired vast amounts of land in the Mohawk Valley, was a successful colonial trader, and adapted well to Native ways. Johnson was eventually appointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the province of New York, and was knighted for his efforts during the French and Indian War, 1755-1760. It was at the start of this war, under Johnson's orders, that Fort William Henry was constructed at the southern tip of Lake George, becoming the northernmost British outpost in the interior of Colonial America. The fort also became the scene of one of the most famous and brutal massacres in North American history, immortalized in James Fenimore Cooper's epic The Last of the Mohicans (Starbuck, 1991:8-11). It was at the end of this war that Molly Brant and William Johnson began their official association.

William Johnson had previously co-habited with a German woman named Catherine Weissenberg. Although he had hired her as a housekeeper at Fort Johnson, they had three children: Nancy, Mary (Polly), and John were all christened at Fort Hunter, under Weissenberg's name only. Although Johnson regarded Weissenberg, who had been an indentured servant, as beneath his social status, he did regard these three children as legitimate offspring (Green 1989: 237). Catherine Weissenberg died in 1759 (Graymont 1979: 417) the same year that Molly gave birth to her and Sir William's first child.

The so-called "marriage" of Sir William Johnson and Molly Brant probably took place solely as an act of consummation. At a time when the presence of illegitimate children was perfectly acceptable, in fact even expected of those who could provide for them, attempts should not be made to try to prove that a traditional legal European marriage took place. The fact that Sir William was not legally married to any other at this time should be some indication as to his feelings towards Molly and their children. At the time of the birth of their first son Molly was about 23, while Sir William was 44 years old. They had seven more children who survived infancy (Wilson 1976: 56; Green 1989: 246; Graymont 1979: 417). The family lived first at Fort Johnson, where Molly was Mistress, from 1759 to 1763 and then, after it was built, at Johnson Hall from 1763 to 1774 (Johnson Hall State Historic Site; Wilson 1976: 56).

It is clear from contemporary records that, for Molly Brant, life at Johnson Hall was far from uncivilized. Her settled and civilised existence contradicted the general view of Natives held by Europeans at the time, a view that perceived Natives as an inferior race and led to their commonly being referred to as savages. Johnson Hall was even more elegant than Fort Johnson, and it was larger. The two-storied, Georgian, white-frame façade was 55 feet long, with four large rooms on the ground floor, a centre hall, and a great staircase. There were two fireplaces, as many windows in the rear of the house as in the front, and a large cellar beneath the entire structure. A single door served as the front entrance, and a similar door at the other end of the hall led to a formal garden. The house was flanked by two fully armed stone blockhouses (Thomas 1986: 67; Thomas 1989: 143).

While Molly Brant had grown up in a Mohawk Village, she was exposed at an early age to European influences through her step-father, Nickus Brant, through William Johnson, and likely through others. As well, aspects of her traditional Mohawk upbringing served her well in her role as Sir William's consort. Iroquois women in their own society enjoyed more power and higher status than did white women in their society (Graymont 1976: 31). Molly was obviously able to successfully transfer both power and status to her position, as she apparently dominated the Johnson household. There are numerous references to her purchasing orders, and to her general control over the estate. It has also been suggested that she took responsibility for the daily affairs of the Indian Department when Sir William was away. Although she was entirely capable, Molly did no housework, as that was the task of the indentured servants and black slaves who worked on the estate and surrounding farm (Green 1989: 237).

It is somewhat puzzling to see a prominent, capable woman deviating from the traditions that provided her power and influence. Surely she would have recognized that the acculturation of Mohawk traditions to those of the Europeans would eventually cause the Mohawk to loose both economic power and political influence in their society (Green 1989: 236). She was, however, obviously happy with her position in both Mohawk and Colonial society; her influence among the Mohawk people benefitted Sir William in his position as Superintendent of Indian Affairs, and it is certain that his position enabled her to maintain her power and influence (Wilson 1976: 56; Thomas 1989: 143; Green 1989: 238; Graymont 1979: 417; Graymont 1976: 31).

A valuable glimpse into the daily routine at Johnson Hall is provided by Judge Thomas Jones, who describes "a kind of open house" always full of Indians and travellers:

from all parts of America, from Europe, and from the West Indies. . . . The gentlemen and ladies breakfasted in their respective rooms, and, at their option, had either tea, coffee, or chocolate, or if an old rugged veteran wanted a beef-steak, a mug of ale, a glass of brandy, or some grog, he called for it, and it always was at his service. The freer people made, the more happy was Sir William. After breakfast, while Sir William was about his business, his guests entertained themselves as they pleased. Some rode out, some went out with guns, some with fishing-tackle, some sauntered about the town, some played cards, some backgammon, some billiards, some pennies, and some even at nine-pins. Thus was each day spent until the hour of four, when the bell punctually rang for dinner, and all assembled. He had besides his own family, seldom less than ten, sometimes thirty. All were welcome. All sat down together. All was good cheer, mirth, and festivity. Sometimes seven, eight, or ten, of the Indian Sachems joined the festive board. His dinners were plentiful. They consisted, however, of the produce of his estate, or what was procured from the woods and rivers, such as venison, bear, and fish of every kind, with wild turkeys, partridges, grouse, and quails in abundance. No jellies, creams, ragouts, or sillibubs graced his table. His liquors were Madeira, ale, strong beer, cider, and punch. Each guest chose what he liked, and drank as he pleased. The company, or at least a part of them, seldom broke up before three in the morning. Every one, however, Sir William included, retired when he pleased. There was no restraint.

Such prolific activity would have kept Molly and her large staff of slaves and servants extremely busy. This circumstance would certainly have provided justification of her title as 'housekeeper,' or manager of the household affairs, a term often used by Sir William in reference to Molly (Thomas 1989: 142; Graymont 1979: 417; Graymont 1976: 31). Again, we must consider this terminology in the context of the period in which it was used. Molly was, in fact, the chatelaine of Fort Johnson and later Johnson Hall: a role of great importance and responsibility throughout history, not merely that of a "cleaning lady"!

Another contemporary visitor to Johnson Hall, an English woman, described Molly Brant: "Her features are fine and beautiful; her complexion clear and olive-tinted . . . She was quiet in demeanour, on occasion, and possessed of a calm dignity that bespoke a native pride and consciousness of power. She seldom imposed herself into the picture, but no one was in her presence without being aware of her." (Wilson 1976: 56; Johnson Hall State Historic Site). It would appear that Molly played the perfect hostess, exactly what Sir William required, but certainly not feckless.

Molly Brant was also known as an expert herbalist, bringing her healing abilities to the household. The large herb garden at Johnson Hall is testimony to her interest in what was a life-long pursuit (Johnson Hall State Historic Site). She was, however, unable to prevent one untimely death. Suddenly, in July 1774, at the age of 59, Sir William Johnson died (Wilson 1976: 56; Thomas 1989: 143; Green 1989: 239; Graymont 1979: 417).

Neither the emotional nor the political turmoil in Molly Brant's life at this time can be gauged. It can be assumed that she took this in stride, moving her family of eight children, who ranged in age from infancy to 15 years, to Canajoharie (Thomas 1989: 143; Thomas 1986: 66; Graymont 1979: 417). It is probable that a number of the servants and slaves from Johnson Hall went with Molly and her family, since Sir William provided generously for them all in his will: a lot in the Kingsland Patent, a black female slave, and £200, New York currency (Graymont 1979: 417; Green 1989: 237; Thomas 1989: 143). Molly wasted no time in reestablishing her influence among the Mohawk, for she established a trading business immediately (Graymont 1979: 417; Johnson Hall State Historic Site).

The American Revolutionary War

Disharmony in the Thirteen American Colonies had been threatening the peace for some time. Quite simply, many American colonists did not wish to pay taxes to cover the cost of King George III's wars. They also argued that they had no representation in the British parliament (Fryer 1980: 12; Petrie 1978: 25). Support for the rebellion and independence by the population of the colony was far from unanimous: About one third supported it, one third was indifferent and the final third remained loyal to the British crown (Fryer, 1980:13). Nonetheless, an organised revolutionary movement developed in the Mohawk Valley in May 1775 (Cruikshank 1984: 1). In the early summer, Guy Johnson and Daniel Claus, sons-in-law of Sir William, took their families and left the Mohawk Valley, along with many other loyal friends. Sir John Johnson, Sir William's heir, remained at Johnson Hall, firmly believing that the problem would be settled peacefully. He was, however, eventually forced to flee (Thomas 1986: 68).

The American Revolutionary War, or War of Independence, brought about fundamental changes in the lives of Molly Brant and her family members. During the initial stages of the war, most of the Six Nations of the Iroquois remained neutral; some, however, took sides immediately. Joseph Brant did his utmost to persuade the Six Nations to break their treaty of neutrality with the Americans, which they finally did in 1777 (Graymont 1976: 25). Apart from the British regulars, there were also provincial regiments, one of which was directed by Sir John Johnson, King's Royal Regiment of New York (Fryer 1980: 63). Through the early part of the war, Molly sheltered and fed loyalists, and sent arms and ammunition to those who were fighting for the King. She is also said to have conveyed intelligence to the British military which resulted in the successful route of American forces at Oriskany in 1777 (Graymont 1976: 26; Green 1989: 239-40). Such actions, along with the advancing patriots, ultimately left her no choice but to flee, as many others had done before her. She left the Mohawk Valley with her family, two male slaves and two female servants in 1777, and went to Fort Niagara. Her younger children were then sent to school in Montreal (Johnson Hall State Historic Site).

Throughout the war Molly Brant made several trips back and forth between Niagara, Montreal, and Carleton Island. The Mohawk from the upper village of Canajoharie took refuge at Fort Niagara, while those from the lower village travelled to Montreal (Tooker 1976: 11) and Lachine (Boyce 1967: 19-21). Fort Haldimand was built at the southwest corner of Carleton Island in 1778 (Cruikshank 1984: 148). Now, more than ever, Molly was expected to use her influence over the Mohawk warriors. She was an intelligent woman, and she used the colonial administration to increase her own political power and to promote the interests of her people. The government similarly used her as an instrument of political control (Green 1989: 240). In describing a large Iroquois force that had gathered at Carleton Island, the commander of the fort indicated that "their uncommon good behaviour [was] in great measure to be ascribed to Miss Molly Brant's influence over them, which [was] far superior to that of all their Chiefs put together" (Wilson, 1976:56; Johnson Hall State Historic Site). Throughout the war, Molly continued to use her influence to steady the warriors, bolster their morale, and strengthen their loyalty to the King (Graymont 1976: 31).

As the war continued, native, loyalist, and patriot settlements were attacked and burned. Thousands of destitute Iroquois made their way to Fort Niagara, suffering from starvation and illness. Compounding the situation, the winter of 1779-1780 was one of the most severe on record (Petrie, 1978:38). Support for the American cause from France, Spain, and the Netherlands, and underestimation by the British of the Americans' determination to gain independence, ultimately decided the outcome of the war. The surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown in 1781 ended the war and forced England to recognize the independence of the Thirteen Colonies (Petrie 1978: 39).

The End of the War

After the war, no provision was made for the Iroquois in the Treaty of Paris of 1783: they were left to conduct their own negotiations (Tooker 1976: 12; Petrie 1978: 39; Quinn 1980: 77). It is known that Joseph Brant petitioned Governor Haldimand on behalf of the Iroquois; it has also been suggested that Molly used her influence on behalf of her people at this time (Green 1989: 241). Eventually, land on the Bay of Quinte was granted to the Iroquois; not all were satisfied, however, and additional lands on the Grand River were requested (Wilson 1976: 57; Petrie 1978: 39-43). The Mohawk who had travelled to Montreal during the war settled on the Bay of Quinte, where they were led by John Deserontyou, while those who had been refugees at Fort Niagara went with Joseph Brant to the Grand River (Tooker 1976: 12).

Life at Cataraqui

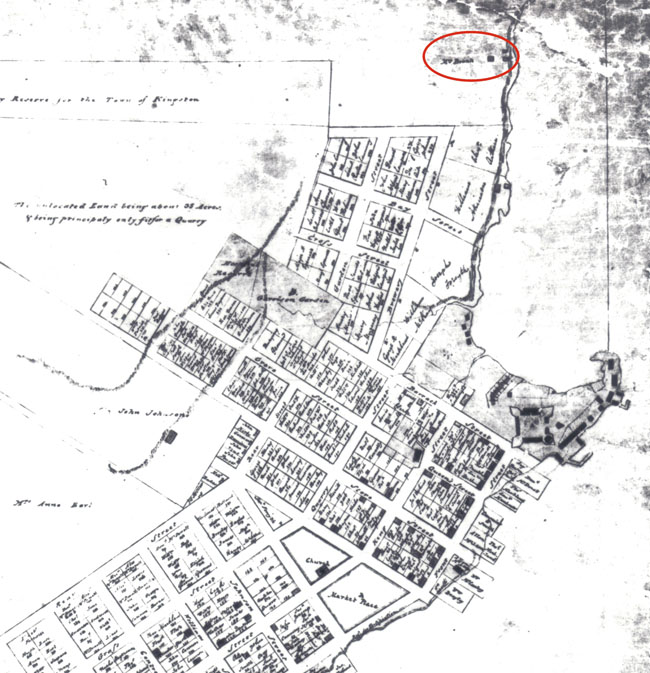

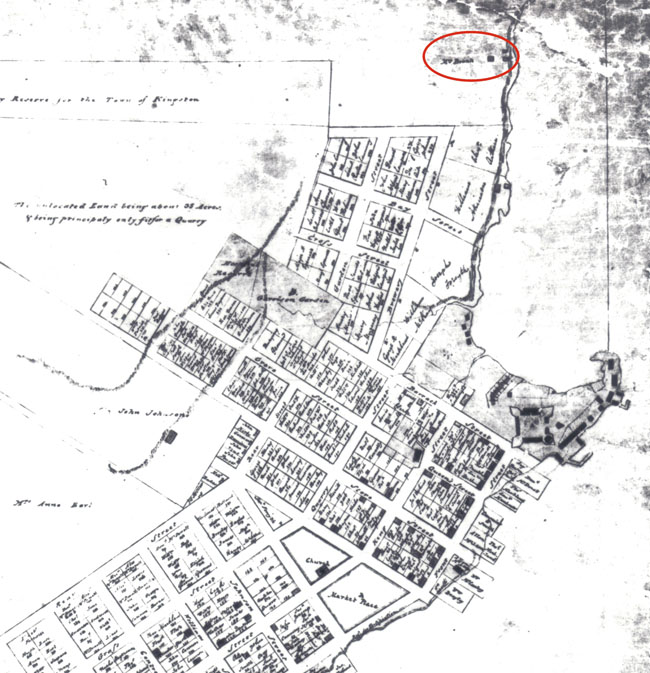

Molly Brant settled at neither place. It was decided in 1783 that the site of the old French fort at Cataraqui, originally selected for the Iroquois, would be a good place for the settlement of the other Loyalists. Arrangements were made for the movement of troops, equipment, and even buildings from Carleton Island, located on the American side of the new border. It was at this time that Molly decided to settle at Cataraqui (Quinn 1980: 78-9; Green 1989: 241). She received a substantial military pension for her service to the King during the war, an amount of £100 (Green 1989: 241; Thomas 1989: 146; Graymon, 1979: 418). It has been suggested that Molly may not have been welcome at Tyendinaga, on the Bay of Quinte, due to animosity between her brother and John Deserontyou; her brother's presence at the Grand River, however, and that of her son George, do not suggest antagonism. As well, Molly's relationship with Reverend John Stuart, who had been with the Mohawk at Fort Hunter (Boyce 1967: 22) and had later settled in Cataraqui, may have influenced her decision. Perhaps the best explanation, however, is the strong traditional Iroquois mother-daughter bond (Green 1989: 241): three of her daughters settled on land that was to become Kingston.

In a letter dated September 10, 1783, from Major Mathews to Governor Haldimand, no objection is voiced to Molly Brant's request to have a house built for her (Cruikshank 1984: 108). Molly lived in the barracks until the house was complete. In a letter dated October 15, 1783, Major Ross wrote to Major Mathews: "I hear that Joseph Brant is exceedingly surprised that no house is as yet built for Miss Molly. I will write to him by the first opportunity that it shall be done as soon as possible" (Cruikshank 1984: 110). As the correspondence continues through this early period of settlement, we learn that a house is also built for Joseph at Cataraqui: (Haldimand to Ross, November 1783) "As it is natural to suppose that Joseph Brant would wish to have a Home contiguous to His sister for the purpose of leaving His family under Her protection when called abroad by War, or Business, I would have a comfortable House built for him as near as possible (but distinct from) to Molly's - it will give them both Satisfaction, and they can be gratified without any very great Expense, as there are so many Workmen employed;" (Ross to Mathews, February 1784) "Captn Brant who is the bearer of this letter seems highly pleased with the favour shewn him by His Excellency in Causing a house to be built for him at Cataraqui which together with Miss Mollys is in great forwardness and to flatter him Still more Some little alteration has been made agreeable to his Wishes;" finally (Ross to Mathews, June 1784) "Captain Brants House 40 foot in front by 30 in depth and one storey and a half complete. Miss Molly Brants House nearly Complete" (Cruikshank 1984: 113, 119, 121).

Unlike the other Loyalists, Molly did not have to draw for lots. The property that she was assigned was Farm Lot A in Kingston Township, along the northern limit of the town. It was only 116 acres instead of the standard 200 acres because it was encroached upon by the Clergy Reserve (Bazely 1989: 4). She was however, as dispossessed as the rest of them: it is probable that she would have arrived with very few personal items. There are indications of her being sent a "Trunk of Presents" by Colonel Daniel Claus, Sir William's son-in-law, as well as being given money by her brother and Governor Haldimand, in addition to another trunk (Gundy 1953: 101).

Historical records and recent writings present Molly Brant as a strong individual who retained her native heritage throughout her life, often to the disdain of her European contemporaries. Molly is a controversial figure because she was both pro-British and pro-Iroquois. She insisted on speaking Mohawk, she dressed in Mohawk style throughout her life, and she encouraged her children to do the same. She argued on behalf of the Iroquois before, during, and after the American Revolution. She sheltered and fed her people. She complained when she thought the government was ignoring the Iroquois (Green 1989: 241). Did Molly Brant disappear into a life of obscurity, no longer intervening on behalf of her people? After the war, the prominent female presence in the public sphere of Iroquois society had been greatly reduced. For Molly's daughters, this circumstance encouraged acculturation, but Molly could rely on her past performance and recognition to maintain respect from the Europeans among whom she now lived (Green 1989: 242). At the age of 47, after a long and difficult war, it is possible to believe that she was exhausted; the few historical references to her life at Cataraqui, however, indicate that, at least to some extent, she maintained her quiet dominance.

In 1785, Molly travelled to Schenectady in the Mohawk Valley, apparently to sign legal documents. It is reported that the Americans wanted her and her family to return, and went so far as to offer financial compensation. The response, the one to be expected from Molly Brant, was that she rejected the offer "with the utmost contempt" (Graymont 1979: 418; Thomas 1989: 147).

The position of minister in Kingston, held by Reverend John Stuart, had for years been supported by the government. In 1791, it was suggested by the Society for the Propogation of the Gospel that the churchwardens in Kingston should support their own minister. The churchwardens then ordered the erection of a church, built in 1792, for which Molly Brant was the only female benefactor, contributing £1.00 (Preston, 1959:lxii, 296). Some time after the construction of the church, an account by an anonymous traveller mentions her: "in the Church at Kingston we saw an Indian woman, who sat in an honourable place among the English. She appeared very devout during Divine Service and very attentive to the Sermon" (Lamontagne 1959: 23).

In 1794 Molly made a trip to Niagara and returned on board the Mississauga with Mrs. Simcoe. Molly was ill at the time, and Mrs. Simcoe indicates in her diary that Molly wanted to go home. Mrs. Simcoe also indicates that Molly "speaks English well and is a civil and very sensible old woman" (Graymont 1979: 418; Thomas 1989: 147). In 1795, Governor Simcoe became ill and was confined to his room for more than a month. According to Mrs. Simcoe, there was only a horse doctor to take care of him; Molly, however, "prescribed a root . . . which really relieved his Cough in a very short time" (Thomas 1989: 147; Graymont 1979: 418).

On April 16, 1796, at the age of about 60, Molly Brant, a true Canadian Heroine, died. She was laid to rest in the burial ground of St. George's Church, located at what was to become the corner of Queen Street and Montreal Street, where St. Paul's Church now stands. Sadly, the exact location of her plot is unknown.

The Fate of the Brant Property

After Molly's death, the Brant farm remained in the family: it was passed on to her daughter, Magdalene Ferguson, and then to another daughter, Margaret Farley. By this time, 1829, the land ownership was being questioned, and the Board of Ordnance attempted to dispossess Margaret several times. Upon Margaret's death, sometime between 1844 and 1846, the property was passed on to her widowed daughter-in-law, Jemima Farley. Jemima maintained the homestead from 1847 to 1874 on behalf of her son and daughter, who were the heirs and great grandchildren of Molly Brant. Jemima Farley is presumed to have been deceased by 1875, marking the end of the Brant ownership of Farm Lot A (Bazely 1991: 17). According to the Assessment Rolls, by 1892 neither of the two Brant homes were standing (Bazely 1989: 13).

Archaeology on the Brant Property

In 1988, archaeological testing was conducted on the site of the new Rideaucrest home as part of the Kingston Archaeological Master Plan Study. In light of the importance of Molly Brant in Canadian history, of the impending development, and of archaeological evidence from the testing, further study seemed appropriate. Salvage excavations were carried out during the summer of 1989 (Bazely 1991: 17).

In general, much of the original site of the Brant homestead had been disturbed by recent industrial activities. The fact that the site remained residential for one hundred and nine years, and was in the possession of the Brant family for ninety-five years, suggests to archaeologists that cultural material should have accumulated. In its earliest years as an industrial complex, only the area beside North Street appears to have been used. The site of the Brant homestead was eventually turned into the Kiwanis Playing Field, and was not disturbed by industry until the property was purchased by Imperial Oil in 1938. It was at this time that the below ground remains of the Brant homes were probably removed, in preparation for the construction of the oil storage tanks (Bazely 1991: 17; Bazely 1989: 25).

The excavation in 1989 focused on two areas concluded during the testing to contain structural remains. One area showed evidence of mortar stains and pieces of flat, cut limestone. Unfortunately little else was found to indicate a structure, and the artifacts had quite a varied date range. The most interesting find was a fragment of native pottery identified as Middle Woodland, dating between AD 600-900. In general, the material appears to date from the late nineteenth century to the present. It is not possible to say for certain whether pre-contact people used this particular area, but we know from other nearby sites (e.g. Belle Island) that they were in the general area during that particular time period (Bazely 1991: 17).

The second area contained a mortared limestone structure measuring 3 x 3 metres. It has been positively identified as one of the two buildings shown on the 1869 Fortification Survey of Kingston, and is most likely the more southerly of the two. This was probably a privy for the Brant homes, which could easily be cleaned out into the then closer Cataraqui River (subsequently partially landfilled for the railway) (Bazely 1991: 20).

Interpreting What Was in the Privy

Excavating within the walls of this structure was like walking on eggshells. It was found to be filled with over 5,000 artifacts, including ceramics, bone, nails, glass, buttons, clay smoking pipes, and a variety of interesting personal items. It was possible to distinguish which layers accumulated after the structure had been demolished, because the artifacts contained in these layers were clearly from the twentieth century. The upper deposits within the privy contained artifacts which can be dated to the mid to late nineteenth century. A lower deposit, beneath a layer of bark, contained artifacts representative of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, probably deposited while the privy was in use (Bazely 1991: 20; Bazely 1989: 44).

Some of the more interesting artifacts found within the privy include: bone combs and hair pins; a lady's finger ring, possibly set with amethyst; an ivory toothbrush; creamware and pearlware ceramic chamber pots; hand-painted pearlware ceramic dishes; crystal stemware; a variety of shapes, sizes, and colours of beads; bone, shell, glass and metal buttons; intact medicine bottles; clay smoking pipes including a detailed painted human effigy bowl; bone from cow, sheep, pig, and domestic chicken, which was probably raised on the site, and from goose, duck, passenger pigeon, and a variety of freshwater and Atlantic fish. Detailed analysis allows us to determine the relative wealth and status of the family within the community: food related items provide information on diet and butchering practices used. Such analysis is the only real way of gaining insights into the personal lives of some of the people who lived on the shore of the Cataraqui River in centuries past (Bazely 1991: 20).

Although it cannot be said absolutely that this privy was constructed and used during the lifetime of Molly Brant, it can be assumed that there would have been privy structures on the property, and that they would have been within easy reach of the houses (a definite consideration due to the severity of winter in this part of Ontario). It is quite common to find privies full of a variety of different artifacts, due to the fact that when privies were no longer in use, they often became garbage receptacles for just about everything, including food refuse. Quantities of ceramics were also deposited during use to help with drainage and to break down faecal matter: this is referred to as percolation fill, the separation of solid and liquid waste. Other privy studies indicate that the proportion of ceramics, particularly of chamber pots, is frequently high, but there is some discussion as to which items come from on-site household garbage and what is brought from off-site (Bazely 1993).

While the Brant privy contained many less expensive ceramic wares, it also contained fine glassware identified as being British military issue, perhaps one of the gifts given to Molly by General Haldimand and Daniel Claus. Other items that might be attributed to Molly Brant include beads, with fifty-two of the small beads being typical of those used in Native beadwork, which might have adorned Molly's traditional Mohawk dress. Bone and ivory toothbrushes, bone lice combs and the amethyst finger ring again point to elevated social and economic status, and even personal preference (Bazely 1993). Many of these items can be viewed at the Kingston Archaeological Centre as part of the Loyalist and Molly Brant exhibits.

In conclusion, more than 200 years after her death, we should continue to honour this exceptional woman. In the words of Ian Wilson, in a past tribute to Molly Brant, "Posterity has done scant justice to this remarkable woman. In her life time she commanded respect from Indian and white alike. Soldiers, statesmen, governors and generals wrote her praise. Her life from the Ohio and Mohawk Valleys to Kingston was not easy. It was fraught with danger and uncertainty and little seemed settled. She survived this turmoil with dignity, honour and distinction as a mother and a leader" (Wilson 1976: 57).

References

Bazely, Susan M.

1993. "Molly Brant, a Loyalist, Too: Her Life in Kingston as Seen Through Archaeology." Presentation made to the Kingston and District Branch United Empire Loyalists' Association of Canada.

1991. "The Last Home of Molly Brant." Newsletter of the Cataraqui Archaeological Research Foundation Vol. 8, Nos. 1&2. Kingston.

1989. Rideaucrest Development Property Mitigation BbGc-19 Manuscript held by the Cataraqui Archaeological Research Foundation. Kingston.

Boyce, Gerald E.

1967. Historic Hastings, Hastings County Historical Society. Hastings County Council. Ontario Intelligencer Ltd. Belleville.

Cruikshank, E.A. and Gavin Watt

1984. The King's Royal Regiment of New York. Ontario Historical Society. Toronto.

Fenton, William N. and Elisabeth Tooker

1978. "Mohawk." Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15, Northeast. Bruce G. Trigger, ed. Smithsonian Institution. New York.

Fryer, Mary Beacock

1980. King's Men the Soldier Founders of Ontario. Dundurn Press Ltd. Toronto.

Gundy, H. Pearson

1953. “Molly Brant - Loyalist.” Ontario History, Vol. 14, No. 3.

Graymont, Barbara

1981. "The Six Nations Indians in the Revolutionary War." The Iroquois In the American Revolution 1976 Conference Proceedings Rochester Museum and Science Center. Rochester, New York.

1979. "KOÑWATSI'TSIAIÉÑNI, Mary Brant." Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Green, Gretchen

1989. "Molly Brant, Catharine Brant, and Their Daughters: A Study in Colonial Acculturation." Ontario History. Vol. LXXXI, No. 3.

Lamontagne, Leopold

1959. "Petticoats and Coifs in Old Kingston." Historic Kingston, Vol. 8. Kingston.

Petrie, A. Roy

1978. "Joseph Brant." The Canadians. Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd. Toronto.

Preston, Richard A.

1959. Kingston Before the War of 1812. Champlain Society. University of Toronto Press. Toronto.

Quinn, Kevin

1980. "Joseph Brant: Kingston's Founding Father?." Historic Kingston. Vol. 28. Kingston.

Starbuck, David R.

1991. "A Retrospective on Archaeology at Fort William Henry, 1952-1993: Retelling the Tale of The Last of the Mohicans." Northeast Historical Archaeology. Vol. 20.

Thomas, Earle

1989. "Molly Brant." Historic Kingston. Vol. 37. Kingston.

1986. Sir John Johnson Loyalist Baronet. Dundurn Press. Toronto.

Tooker, Elisabeth

1981. "Eighteenth Century Political Affairs and the Iroquois League." The Iroquois In the American Revolution, 1976 Conference Proceedings. Rochester Museum and Science Center. Rochester, New York.

1978. "The League of the Iroquois: Its History, Politics, and Ritual." Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15 Northeast, Bruce G. Trigger, ed. Smithsonian Institution. New York.

Wilson, Ian

1976. "Molly Brant: A Tribute." Historic Kingston. Vol. 2. Kingston.