The Fur Trade

The French regime in Canada began in the early 1500s with the establishment of commercial bases, missionary outposts, and permanent settlements. France controlled two of the main entries into the fur-rich interior, the St. Lawrence and the Mississippi, while England controlled the other two, Hudson Bay and the Hudson River. Both the French and the British had to contend with the Iroquois Confederacy, which represented a very powerful military force in the southern Great Lakes region.

Many native tribes were eager to exchange food and furs for European goods: as suppliers, they greatly influenced the economic impact of the fur trade. This influence made it necessary for both the French and British to form alliances with native groups.

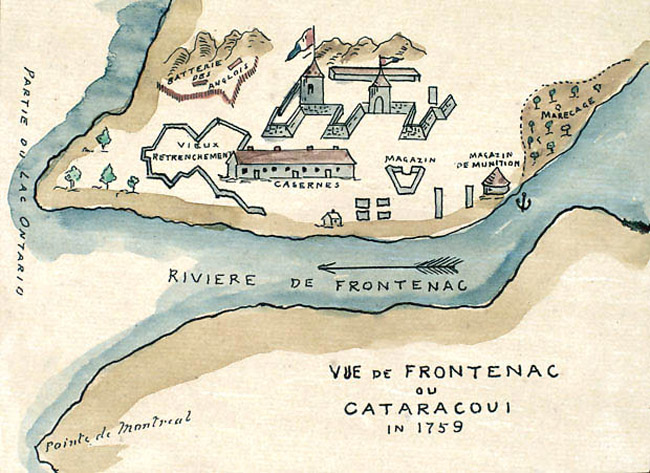

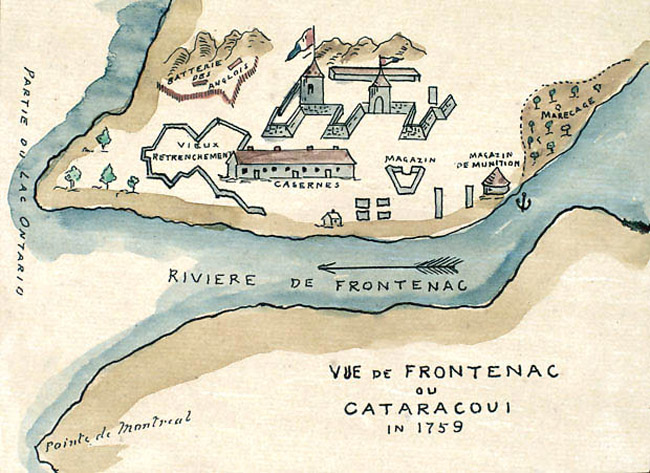

For the most part, trading posts consisted of a few huts surrounded by a stockade, located on a river bank near an Indian village. Fort Frontenac, a trading and military post located in what is now downtown Kingston, had more substantial fortifications built of limestone. It contained barracks for troops and military stores, as well as trade goods. Voyageurs travelled to the western posts, including Fort Frontenac, carrying European goods to exchange for furs. These highly favoured goods, including metal knives, axes, guns, pots, coloured glass beads, and woollen blankets, provided incentive for Natives to take their furs to the fort.

The Settlement

Scattered along the St. Lawrence Valley in the sixteenth century were Iroquois villages. Due to warfare in Europe and the absence of financial incentives, the French did not establish permanent European settlements in the area until the early 1600s. At that time, the growth of the fur trade encouraged permanent settlement at the present-day sites of Quebec City and Montreal.

Seeking to strengthen France's control of the Great Lakes region, Comte Frontenac established the first European settlement in the Kingston area in July of 1673. The west bank of the Cataraqui River, where it joins the St. Lawrence River, was selected as the site of Fort Cataraqui, subsequently renamed Fort Frontenac. The site was chosen for its strategic location, and the presence of a good natural harbour.

In 1675, Louis XIV of France granted four leagues of territory along Lake Ontario, as well as a section of the Thousand Islands, including Wolfe Island (Grand Isle), to Robert Cavalier, Sieur de La Salle. The French surveyed a portion of Wolfe Island, but there is no indication that this area was permanently settled during the French period.

Although the French were able to maintain Fort Frontenac through much of the remainder of their reign in Canada, the poor agricultural soil and hostile pressures from both the region's native communities and the British served to discourage more intensive settlement of the area by the French. There was, however, a small settlement, including several Iroquois longhouses located around the fort. Recollet missionaries ministered to this small community.

The Iroquois Wars

The Iroquois nations located on the south shore of Lake Ontario were anxious to gain control of lands to the north of the lake, the possession of which would allow them readily to exploit the northern hunting grounds where beaver were more plentiful. The Iroquois received far less for their furs from the French in Montreal than they did from the British and Dutch in Albany and New York, so they continued to hunt in the rich French territories while trading their furs with the British and the Dutch. This circumstance brought the Iroquois into conflict with the French.

Hostilities between the French and the Iroquois began slowly, but soon Fort Frontenac was at the centre of the troubles. By 1687, religious, commercial, and political concerns made war inevitable. In preparation for an attack on the Iroquois, Gouverneur Denonville had the Jesuit missionary, Father Lamberville, invite the principal Iroquois chiefs to Fort Frontenac to discuss peace. When the French force arrived at the fort they seized the visiting Iroquois and sent them to work as slaves on the war ships of Louis XIV. The French destroyed several Iroquois villages on the south shore of Lake Ontario before returning to Montreal in mid August, 1687.

The Iroquois retaliated to the French acts of aggression by attacking French settlements; many habitants were killed or taken prisoner. Food became scarce among French settlers during the Iroquois sieges, and by February of 1688, ninety-three members of the garrison at Fort Frontenac had died of scurvy. The massacre at Lachine occurred in August of 1689, and by November of that year instructions came from the Gouverneur to destroy Fort Frontenac and return to Montreal. This was Denonville's last act as Gouverneur: he was replaced by Comte Frontenac who was returning for his second term as Gouverneur.

Peace talks which took place at Quebec in 1694 between the French and the Iroquois included a proposal for the rebuilding of Fort Frontenac, which ultimately took place in the summer of 1695. The peace, however, did not last, and the Iroquois resumed their raids the following April. That summer, a major offensive was launched from Fort Frontenac against the Iroquois, causing the latter to sue for peace. In 1700, two years after the death of Comte Frontenac, peace was finally obtained, along with assurances for the continued operation of Fort Frontenac.

French-British Conflict

Economic and political rivalry between France and Britain erupted into a series of conflicts between 1688 and 1763 in both Europe and North America. In North America the disputes centred around territorial claims, the fur trade, and fishing rights. Fort Frontenac was part of a line of posts that defended and supplied the western frontier of New France. The British saw the fort as an obstacle to their control of the fur trade, while the Iroquois perceived it as a restraint on their interaction with other native groups.

Until the 1750s, Fort Frontenac was largely neglected by the French, as maintenance and transportation costs associated with the fort dramatically decreased the profits to be gleaned from the fur trade. Despite numerous conflicts and treaties, the fundamental problems of boundaries and control of the fur trade had not been resolved by the 1750s. In anticipation of a final conflict, repairs were made to Fort Frontenac and additional personnel were sent there.

On August 25, 1758, a British force under Lieutenant-Colonel Bradstreet landed one mile away from Fort Frontenac. After the failed escape attempt of two vessels and a day and night of continuous artillery fire, the French were forced to surrender. Bradstreet allowed the 110 men, women, and children to return to Montreal, ransacked the fort, and abandoned it. This effectively ended the French occupation of the Kingston area. France, unable to compete with Britain's naval might and superior numbers, eventually surrendered to Britain in 1763.