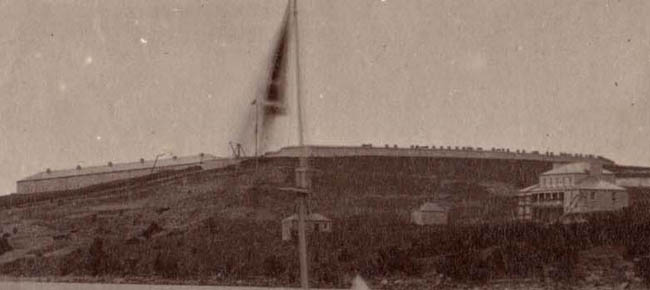

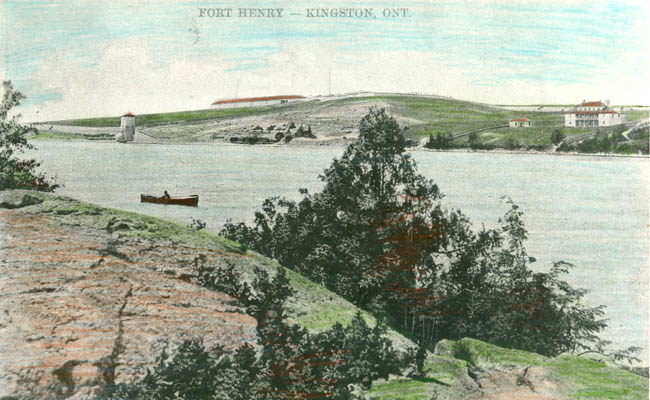

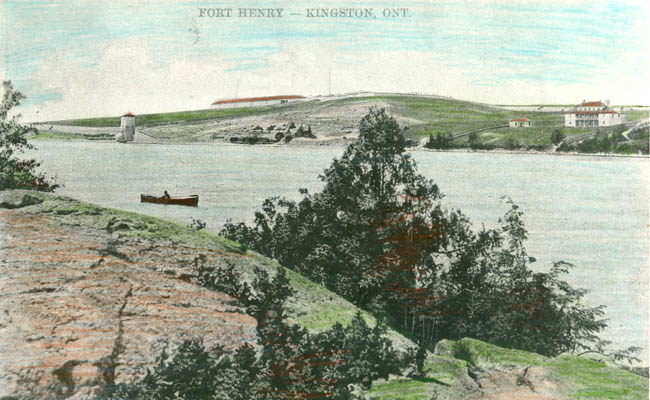

In 1827-1828 the Fort Henry Garrison Hospital was built on the east side of Point Henry to complement the army’s Regimental or General Hospital, which was located in the town. Its purpose was to serve the artillery and infantry detachments barracked at Fort Henry, which commanded the height opposite the town and harbour, on the east side of the Cataraqui River. It was situated at some distance from the garrison barracks it served, and it was isolated from the surrounding community by a palisade and guardhouse sentry. The relationship between the isolated hospital site and the fort itself may in fact be reflected in the purpose of the hospital, that of providing isolation from disease on contagion.

When the British garrison marched out in 1870, a permanent Canadian militia was created. Its small size meant the Garrison Hospital became redundant, and it was converted to barracks. It was ultimately abandoned and remained so through the early decades of the 20th century - occasionally visited by RMC cadets on field exercise. At some point the Dead House was demolished. The hospital property was leased by the Department of Militia and Defense to civilians who rapidly populated the shoreline from Cartwright’s Point to Fort Henry with cottages. The stone guardhouse was used by cottagers, but the hospital building itself remained derelict, visited occasionally by transients, and in November 1924 the hospital was destroyed by fire. During the reconstruction of Fort Henry in the mid-1930s the hospital ruins were surveyed with the apparent intention of including it in the overall historic reconstruction, however with the outbreak of WWII and Fort Henry being used as an internment camp, the fire gutted garrison hospital was deemed a nuisance building and demolished.

Excavations took place at the Garrison Hospital over the course of three seasons of the “Can You Dig It?” program (2000-2002). The project was designed to fulfill two main objectives, research and education. From a research perspective the project objectives are to obtain information on the extent and condition of cultural resources in the vicinity of the ca. 1828-1924 hospital, and evaluate their significance for further interpretation.

At the time of the excavations at the Garrison Hospital site, very little was known of the nature of archaeological resources at Fort Henry. Salvage archaeology conducted in 1994 by consultants, as a result of new sewer installation, revealed aspects of somewhat undisturbed to greatly disturbed cultural resources. Little in the way of 19th century occupation was observed, while the impacts of the 1936-1938 restoration were duly noted.

The education program is designed to promote the value of conducting archaeological research and included a variety of hands-on activities. These provided participants with instruction in the methods of archival research, excavation, analysis and interpretation, and display of recovered information. A secondary objective is the promotion of the Kingston Archaeological Centre and the Fort Henry Museum and their resources within the community, as well as throughout the province.

Three discrete locations were investigated in 2000: the general vicinity of the hospital structure; the Guard House structure and immediate vicinity; and the location of the Dead House.

Excited by the find of metal roofing directly below a collapsed brick wall and intact evidence of the fire, the exact location of the hospital remained unknown, but it was clear that it was close. To improve safety in a nearby unit an additional unit was opened up, and it slowly exposed the west wall of the hospital. The dominant artifact types are ferrous including nails and roofing fragments, and two Royal Canadian Artillery buttons. There were also large amounts of bottle glass, dating to the 20th century. There was no evidence of pre-fire occupation and use of the hospital. During the 2001 season four units were placed at various points around where the hospital was projected to be. Again in only one unit was the hospital foundation encountered, the south wall of what was determined to be the south wing. The ditch, or covered way was also identified as was the north wall of the privy. Large amounts of demolition rubble were noted, but as previously, pre-fire occupation layers were not identified.

At the Guard House it was a different matter, since the building is extant. At the southeast corner it was unclear how much impact the addition to the Guard House had on evidence of earlier occupation, but there was clearly some disturbance. Fragments of a Royal Regiment of Artillery shako badge were recovered here. Referred to as the Regency pattern, it dates from 1816 to 1828. Buttons of the 34th Regiment of Foot or Border Regiment and 43rd Regiment of Foot or Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry were also recovered in this area. Both regiments remained in Kingston for only a month, the 43rd in June 1838, travelling by the Rideau Canal, and the 34th in May 1841. Royal Artillery buttons from the Victorian period were excavated on the south side of the Guard House. On the north side, close to the existing door, an 1844 Bank of Montreal Half Penny token was recovered. These date from the earliest period of the hospital through its British military use. In 2001, one excavation unit from the previous year was re-opened and continued and one new area was investigated at the northwest corner. Little additional structural data was collected, but it was apparent that there have been several restoration and maintenance episodes, including that of the 1936-38 restoration.

Other interesting artifacts that illustrate a multi-period, mixed use of the site are a golf club fragment and parts of a flash cube. Of the artifacts recovered from the exterior of the Guard House the dominant types are metal including nails and other hardware items. Some ceramics were encountered, which fit the British military period well and include a small amount of pearlware, larger quantities of refined white earthenware, and small amounts of vitrified white earthenware. The largest quantities of smoking pipe fragments were recovered from around the Guard House, perhaps an indication of a common past time. Again, there are large amounts of bottle and window glass. Evidence of occupation at the Guard House, while somewhat disturbed, contained the strongest elements of the military period from the site.

The final area to be investigated was the Dead House. This was perhaps the most impacted by cottage and picnic activities and provided very little cultural material to assist in interpreting its use over time. Most of the recovered material consists of modern nails and bottle glass. In 2001, intensive excavation of the Dead House, consisting of four units confirmed that the area had been seriously impacted during the cottage period. It was determined from both archival and archaeological evidence that a cottage structure had been built on top of the Dead House. This had quite effectively removed all evidence relating to the construction and use of this feature.

There has been a great impact on the hospital remains caused initially by the fire and the subsequent demolition of the building. It is likely that pockets of evidence of the occupation and use of the hospital remain hidden below the rubble. Excavated evidence has provided a specific location for the hospital. The exterior of the Guard House has provided the best occupation evidence during the military period as well as information on the condition of the foundations of the structure. Investigations at the Dead House reveal that it was in use for a short period of time and has been essentially removed from the landscape through demolition, scabbing of building materials, and new construction and subsequent demolition. The “clean” nature of the area suggests that either cottaging activities and subsequent scrounging completely removed all cultural material related to its use or the use itself left behind little or no material evidence. There is no doubt that the physical isolation of the hospital compound put severe limits on the site formation processes that allow significant accumulations of cultural material.